The path to freedom could no longer be stopped: the Romanians now demanded independence and in 1857 the election for the dīvān resulted in a triumphal victory for the nationalists. It is due to M. Kogălniceanu and his determination that the Paris Conference of 1858 recognized, albeit with many reservations (and without affecting the formal sovereignty of the Porte), the constitution of the United Principalities of Wallachia and Moldavia. A year later, playing on the indeterminacy of an article in the Parisian protocol, the two assemblies voted for the same name and Colonel A. Cuza he was elected prince of both states with the name of Alexander John I. Progressive liberal, Cuza carried out some fundamental reforms, regardless of the fierce opposition of secular and religious conservatives. The agrarian reform, a “European” code, the extension of suffrage, the confiscation of ecclesiastical goods and the emancipation of the peasants, represent the most striking aspects of a far-reaching modernization work. But in 1866 the conservatives carried out a coup and Cuza was replaced by a German prince, Charles of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen.. By 1862 the new state had taken on the name of Romania and Bucharest had become its capital; however, the formal sovereignty of Turkey remained. To bring it down it was necessary to wait for the outbreak of the Russo-Turkish war of 1877: Romania sided with Russia and Charles officially proclaimed full Romanian independence (May 9, 1877). On that occasion, Ion Brătianu proved to be a skilled minister, who by making the small Romanian army intervene directly was able to sit at the table of the Berlin Conference (1878) and therefore have international recognition there. Romania became a kingdom and Charles was crowned king (1881) with the name of Carol I. It was a long reign (Carol died in 1914), essentially stable, marked by joining the Triple (1883) and Germanic influence.

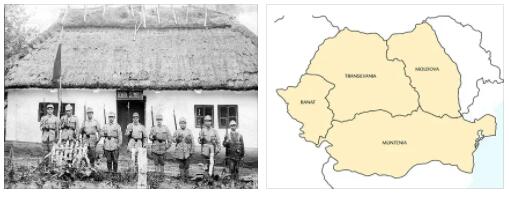

The army, trained in the Prussian style, was greatly strengthened, so it gave excellent proof of its qualities during the Second Balkan War (1913) which resulted in the conquest of Dobruja. But the strictly conservative approach, inside, provoked the outbreak of bloody peasant uprisings (1888-1907) complicated by economic difficulties in the years at the turn of the century. Like Carol I, even his nephew Ferdinand I (1914-27) could count on a shrewd minister, Ioan IC Brătianu, who, at the outbreak of the First World War, managed to impose on the king, a pro-German, to join the Entente (1916): the long, bitter years of the conflict ended in fact with a triumph. The initial military disasters and the occupation of two thirds of the territory (including Bucharest) by the Austro-German troops were rewarded by the final peace treaty, which doubled the Romanian territory with the annexation of Transylvania, Bucovina, Bessarabia, Dobruja and part of the Banat. According to Ehistorylib, the new “Greater Romania” (România Mare) multiplied the population by incorporating important Russian, Ukrainian, Bulgarian, German, Jewish, Hungarian, Serbian minorities: almost a third of the total residents were not Romanians. Furthermore, in 1918 the country found itself bordering on states (and including minorities, often irredentist) such as Russia and Hungary in the throes of dramatic revolutionary convulsions. In reaction, Romania felt like a “border mark”: the anti-communist struggle invested all aspects of Romanian life and the invasion of Hungary by Béla Kun (1919) where the Romanian troops crushed that revolutionary experience, was emblematic. In spite of the difficulties, the first years of “Greater Romania” were still marked by moderate liberalism: but the authoritarian degeneration, also underway in many parts of Europe, would have been rapid and violent. Beyond the enthusiasm and official rhetoric, the country was poor, almost devoid of industry, lacking in the most elementary infrastructures. The assault by foreign capital (especially French) on industrial resources (especially oil) gave way to corruption, court interventions, scandals. The leftist revolutionary propaganda played a good game on the destitute masses, but above all the demagogy of a nationalist, anti-Semitic party inspired by Italian fascism, the Iron Guards. The country slipped into chaos. To complicate matters, a serious dynastic crisis intervened on Ferdinand’s death. His son Carol, guilty of having married a Jewess, was expelled from the succession in favor of his nephew Michele (1927-30), who in turn was taken out of the way by his father with a stroke of his hand. Carol II found nothing better than to establish the strong way: arrests, shootings, dissolution of parties followed one another, until, in 1938, the same Parliament was suppressed and the power entrusted to a far-right National Revival Front assisted by a corporative chamber.

But the troubles were not over: the dark clouds of irredentism were gathering over Romania, which also found support in Italy and Germany. In 1940 following the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact the country lost Bessarabia and Bucovina (passed to the USSR to form the autonomous Republic of Moldavia), Transylvania (to Hungary) and part of Dobruja (to Bulgaria): altogether almost a third of its territory. Hundreds of thousands of refugees in pitiful conditions poured into the capital, while acts of violence and political terrorism multiplied throughout the country. Faced with this explosive situation, on September 5, 1940, the king summoned Ion Antonescu, former Chief of Staff, to the government, who was ousted in 1939 because he was too authoritarian. Antonescu in less than twenty-four hours transformed Romania into a fascist state. Carol II was forced to abdicate in favor of Michael (September 6) and the infamous Iron Guards led by Horia Sima became the one party. Days of blood followed in which the Iron Guards carried out authentic massacres of opponents and violence of all kinds, especially against the Jewish population. In January 1941 they even tried to overthrow the government but were, in turn, fiercely suppressed. Meanwhile, Romania was declared (September 14) a “legionary state” and Antonescu proclaimed Conducǎtor (duce). Then the country had no more history. Axis satellite (in November 1940 it joined the Tripartite) in June 1941 declared war on the USSR by sending his troops alongside the advancing German ones: he reoccupied Bessarabia and annexed Transdnestria, with the city of Odessa, up to the Bug. In 1943 the Soviet victory in Stalingrad and the Italian armistice of Cassibile they induced Romania to make diplomatic contacts with the Allies in order to save the regime, but it was in vain hope. The “legionary state” collapsed even before the arrival of the Soviets; King Michael arrested Antonescu, whose regime was replaced by a popular government which signed the armistice (23 August 1944) and sent Romanian troops to fight against the Germans in Hungary. With the signing of the peace treaty in Paris (10 February 1947), Romania returned the territories occupied in 1941 to the USSR, but at the same time regained Transylvania from Hungary.